THE BANDIT QUEEN: A TRANSNATIONAL MOVIE REVIEW

Art Madsen, M.Ed.

This was, in the true sense of the term, an "authentic" film from India, featuring all of the beauty, violence, savagery and profundity of the Sub-Continent, interwoven with magnificent cinematographic effects, camera angles, contrasting of color, montage, flashback, indeed, virtually every technique known to experimental Western Film. Yet, the production also displayed a special flair for the unexpected, the radical and the shocking.

Based on an actual story of banditry in Utter Pradesh (India) in 1981, nearly bringing down the State Government due to problems of insecurity and the dynamics of voting, this film portrayed the customary practices of the lower castes in India: child weddings, fealty to patriarchal values, bowing in humility to authority, and the day-to-day struggle of survival.

Specifically, it dealt with the life of a young girl, Phoolan Devi, wedded by force to an older man who compelled her to have intercourse with him, at age 11, mere hours after their marriage.

The girl escapes, runs wild throughout the countryside attempting to affiliate with one village after another, but is rejected by village elders as a "temptation" and as an "evil omen". Ultimately, now a grown woman, she resorts to banditry, in the company of a gang of thieves and ruffians, who display, again on balance, a sort of rustic appeal.

Camera techniques, excellent production strategies and good dialogue win over the viewer's sympathies with the male hero, Vareem, a rough-hewn, but humanistically oriented bandit, who dies in a dramatic scene in Phoolan's arms, which could easily pass for the cathartic release of the entire film. This climactic event is further described below.

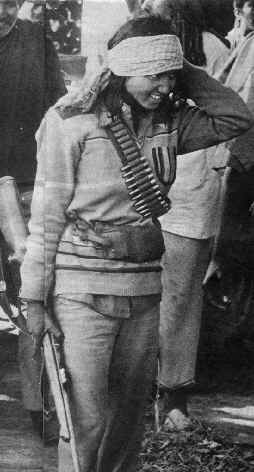

Embarked on a life of revenge and violence, raped multiply in brutal scenes, stripped naked in front of entire villages, regaining her dignity and authority, the heroine, the "Goddess/ Bandit Queen" is honored at a public ceremony when she acknowledges, finally, after a vengeful massacre involving the slaughter of 22 arguably innocent villagers, that perhaps the State is a legitimate authority. She is pardoned by the Governor and passes into legend.

The film is severely lacking in verisimilitude from a psycho-dynamic viewpoint, interpreted by Western Standards. In the Western World, fortunately, modern psychotherapeutic intervention calls for rehabilitation of rape, incest and molestation victims and condemns the outrageous notion that sexual offenses should be punishable by death, or even by ostracism. The "collateral damage" caused by Phoolan, i.e. the death of 22 by-standers who may or may not have participated in the initial assaults on her, however reprehensible, was clearly disproportionate to the harm, perhaps considerable, done the young lady, ... whose make-up and hairdo in the film, we might add parenthetically, seemed to recover miraculously after each animalistic episode of "group-invagination." These inconsistencies were primarily the Director's fault.

Subtle themes and messages abound. Among them are issues of feminism, of social structure, of authority and self-empowerment.

Yet, the brutality of force, within the sexual context, is, only once, offset by the film's wildly enrapturing sequence of what could pass as "real love" between Phoolan, the Bandit Queen, and her charismatic hero, Vareem, who dies clutched to her bosom, a victim of three shattering bullets fired by an arch-rival, angered by Phoolan's having spurned him earlier in the film.

Sophomoric as this point may seem, the whole notion of caste is powerfully portrayed: rights are minimal for those of low caste; and, conversely, those of upper caste enjoy lives of privilege and power.

Tender and lightly humorous scenes between Phoolan and her cousin do, on occasion, provide a modicum of relief for the spell-bound viewer.

Emerging from this film, one is assuredly a little queasy, but enlightened. The poverty and misery of India are clearly compounded by social customs not extant even in Equatorial Africa or in Latin America.

Viewed as an anthropological document, this production portrays the "condition of humanity" as pointedly retrograde.